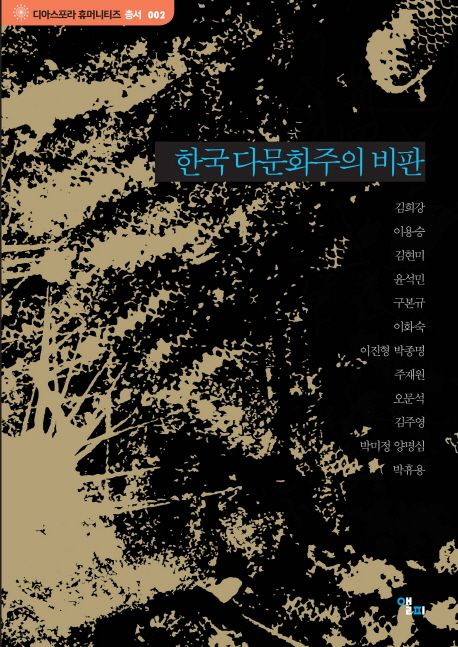

Diaspora Humanities Series, Vol. 2

Our Concerns in the Era of Post-Multiculturalism

In response to the currents of placelessness that characterize the age of globalization, the Diaspora Humanities Series of the Center for Asia & Diaspora at Konkuk University critically reflects on the various problems accompanying mobile forms of life and seeks to rethink the world as a place for human living. It is therefore no coincidence that the second volume of the series addresses our most immediate diaspora: a critique of multiculturalism in Korea.

Multiculturalism began to be implemented as a state policy in Korea in the mid-2000s—little more than a decade ago. Foreign immigration was actively promoted by the government as a solution to declining birth rates in rural areas and labor shortages in so-called 3D (dirty, dangerous, and difficult) industries. Yet even in today’s Korea, with over two million foreign residents, discriminatory perceptions and hostile attitudes toward migrants and their cultures remain deeply embedded as sources of social conflict. This book directly confronts these internalized forms of discrimination and the cultural politics that sustain them.

Are Migrants Also Our Citizens?

The case of Jasmine Lee, a Filipino-born woman who became a proportional-representation member of the National Assembly for the ruling party in 2012, symbolically illustrates the changes taking place in Korean society’s understanding of “multiculturalism.” At the time, the ruling party actively featured her in its election campaign; however, by the 2016 election, not a single migrant candidate was nominated, and hostility—going beyond personal criticism of Lee—has continued to the present. Korean society has thus entered what this book terms the “era of post-multiculturalism,” a period in which multiculturalism has lost its appeal within both government policy and public discourse.

While acknowledging that the ideal of multiculturalism lies in respecting cultural differences and identities and recognizing the civic and cultural rights of minority groups, this book begins from the premise that its reality has proven far more capable than expected of threatening social and political integration and generating cultural conflict. From this starting point, the volume theoretically examines the problems inherent in multiculturalism, including issues of citizenship, and analyzes from multiple perspectives how multicultural discourse has been formed and has functioned in Korea. In doing so, it seeks to respond to the “drifting and crisis of multiculturalism” unfolding here and now.